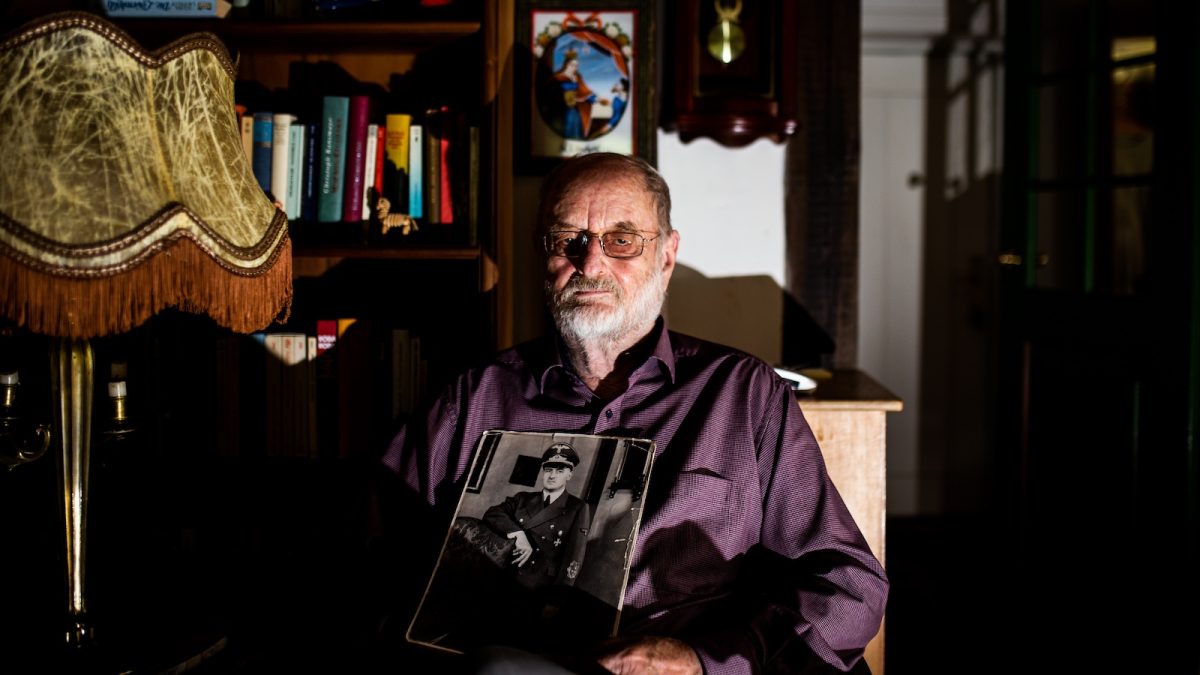

“My father was not a Jew-hater but a careerist” – an exclusive interview with the son of a Nazi mass murderer

During his early childhood years, he was driving his toy car along the corridors of Wawel as the renaissance royal castle of Krakow was the residence of his father, Hans Frank, the governor-general of Nazi-occupied Poland, one of the Nazi war criminals executed after the Nuremberg trials. The life of Niklas Frank, 81, is about nothing but penitence: what should a son do when his father was responsible for the mass murder of millions of Jews and Poles? He can, at least, speak about it – like he did for Válasz Online, in his first discussion with a Hungarian media outlet. An exclusive interview, recorded in a little village of Schleswig-Holstein, about German remorse, forgiveness and about the right of criticizing the current Polish government as the son of a Nazi mass murderer.

– Are you proud of being German?

– I love Germany but I don’t trust the Germans. Germany is a beautiful country with a population of about 80 million: 20 million of them are really democrats – most of them very passive – but the other 60 million are prepared to have another dictatorship, or at least would not fight against it if it came.

– It sounds a bit odd because Germany is said to be the role-model of democracy, especially compared to the populist-led UK or US let alone some Eastern European countries. Howcome you still have this distrust?

– We have built a lot of monuments to our victims which was a great act of propaganda. The silent majority has never really acknowledged what we have done to millions of innocent people: they hide it, somehow forget it or don’t want to speak about it. We are not people of empathy, we never set ourselves in the place of a Jew who has children and suddenly some guards are coming and throwing the family out of the house, pushing them to a truck and sending them away in cattle cars then, at the ramp of Auschwitz, they take away his loved ones. Putting your own loved ones in such a situation – this hardly happens in Germany. Whenever I speak to my friends and the word Jude comes up, everybody is suddenly so reluctant, they cannot endure the hurt of our parents’ and grandparents’ crimes.

– Is it something Germanic?

– When it comes to German history and the holocaust, I don’t want to compare it with other mass murders because it is always a trick to minimize our behavior.

I don’t want to say guilt because no now-living is personally guilty – and guilt is always something personal. One can be guilty also by looking away, like millions in Germany during the Third Reich. We are not guilty but we are not prepared to acknowledge what we have done – besides all the monuments. Our historians, on the other hand, have done an excellent job: there is no crime of the 20th century which has been so thoroughly researched. But the silent majority gives a shit on it.

– If historians have done such a great job then why do you think that 75 per cent of your compatriots would accept another dictatorship?

– I am living in Germany for 81 years and I could look around for 60 years. Therefore I have different access to my people than a foreigner can have. The Germans first obeyed Hitler and when he and his bunch of criminals – including my father – were beaten, the allied forces came and we were told we had another way of life called democracy. The same way we obeyed Hitler, we are obeying the new democracy: it is not coming by heart. On the other hand I have to accept, and I am very happy about it, that nowadays we have the best democracy Germany ever had but it is like a swamp: it is easy to sink. I was happy when the EU was built up because the countries Germany have invaded during her history had the reason to take umbrage against us. And yet, we have the problem with Poland – with that bloody Kaczyński –, with Hungary – with that bloody Orbán –, with Austria, with France’s Le Pen and also the Czechs with that unbelievable prime minister who is pouring EU money on his own factories. We are now without any fences that were built around us and we are the only splendid democracy but our right-wings are smelling there is something they can do towards those authoritarian governments.

– I doubt that even the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party would accept Mr. Orbán’s or Mr. Kaczyński’s style of leadership.

– It is far deeper. AfD is now in every German state parliament – consequently in every state’s cultural department – and they are quietly changing the culture. Just like in Poland with the museums and the exclusive preference of the Polish resistance by cutting down everything else. They are doing it in a more educated way instead of the long-lasting slogan of “let’s kill them”. This is a real but invisible danger.

– I wonder what would a Pole say after finding out that the son of Poland’s Nazi governor-general is criticizing his country’s government.

– I did it some years ago too when I was interviewed by a Polish journalist. As far as I heard he had some problems because some government people were upset and suggested “this bloody Frank should shut up because he has nothing to do with us”.

– Do you understand their sentiments?

– I do. The British and the American army were full of Polish soldiers fighting against Germany. I don’t think, however, that these people – who gave their lives for Poland’s independence – would be satisfied by seeing it is not a democracy anymore and Kaczyński is eroding everything that makes a democracy strong.

– As for Poland, do you recall anything from growing up in Wawel, the royal palace of Krakow where your father’s governorate was headquartered from?

– I remember driving my little car and hurting people as I came around the corner knowing that nobody can do anything against me because I was the son of a powerful man. As a child, you find it our very early. Not to mention the gifts my parents got. We knew exactly that our father was powerful and he behaved like that.

– In your book about him, entitled The Father (Der Vater), you also mention a scene of driving around the Krakow ghetto.

– I only remember that one visit I wrote about: there was a bunch of people and all looked very sad, including the children. Probably we drove around the ghetto more often.

– Having it just underneath your castle, you could have looked like a royal family with its subjects.

– I had a live reading of my book in Krakow and, during the discussion afterwards, a lady of my age stood up and told me: “Mr. Frank, if you could imagine the fear with which we were passing by the Wawel!” My brother Norman, who was 11 years older, has experienced it. He was playing football with other young German guys and suddenly one of the boys said: “Oh, they are shooting Poles again.” They heard them singing the national anthem. They ran a few corners out of the park and the saw the freshly-shot bodies of some 30 Polish hostages – because a German was killed by the resistance. My brother went home to the Wawel, had lunch with my father and asked him: “Daddy (Vati), what happened down there? I have seen killed people in a row on the street.” And the powerful man, my father, threw down his knife and fork, jumped from his chair and, by screaming to my brother: “I don’t want to hear anything about this!”, he ran out of the room. He knew exactly what happened – which was the reason of that lady’s fear.

– Wasn’t your father proud of what they were doing?

– He was proud of his government but surely had no power over Himmler’s SS. His dream was a pyramid-shape government, having himself atop, but Himmler always interfered. Nevertheless,

he was the top guy who, as a deputy of Hitler, had his signature on every law published in the official journal therefore was responsible for every murder committed by the SS.

He knew exactly what was going on and that he was serving a criminal government – having read some of his cruel statements, he was a mass-murderer himself.

– Why was he stationed in Poland?

– That’s one of the mysteries. Politically speaking, he was a dead man when Hitler took over the power in Germany in January 1933. Before that my father was very close to him because he was his personal advocate. After taking control, Hitler had to fear nothing anymore therefore the only influence my father had left was on jurisdictional issues – he was minister of the Reich but without any portfolio, just to get some money. I think he was the most surprised person in Germany when he got the call from Rudolf Hess, after we have invaded Poland, that he should come onboard Hitler’s train in Upper Silesia where they had a short discussion of about 10 minutes after which he was appointed Governor-General. He went home, kneeled down in front of my mother and said: “Brigitte, you will become the queen of Poland!” I think Hitler knew exactly the doggish character of my father: that he wouldn’t cause any problem.

– Was it an option to say no to Hitler?

– For sure. He shouldn’t have gone to the resistance but, after a few month, only should have brought some medical recommendation and saying: “My Führer, I love you, I love your movement, I love the invasion of Poland but look at this test, my heart, I cannot do it unfortunately!” Nobody would have shot him. He was a bloody, cold careerist.

– After invading Poland, did your father have any idea that, in just a few years, millions would be murdered under his supervision?

– He must have had, not only an idea but knowledge, because after 1933 the fight against the German Jews became harsher, the existence of concentration camps was already known. Top Nazis were bubbling privately, everybody knew what would be going on with our urge to go to Eastern Europe. That was clear for him.

– You also wrote in your book that, especially after the turn in Stalingrad, he became decreasingly aggressive towards Poles…

– … he never hates the Poles. It was the ideology he followed and he was a cold careerist. My sisters told me later that back home we never spoke anti-Semitic and we were a funny, loving family. He wasn’t a Nazi ideologist but it helped him to make a career.

– Are you saying that he did not hate the Jews either?

– In his youth diary there is no mention about hatred against the Jews but against the French because they took away the German girls. He was for sure anti-Semitic to the extent most Germans are.

– Was his probably most infamous sentence about the Poles – “we must not be squeamish when we hear the figure of 17,000 shot” – a careerist statement too?

– Yes. He always wanted to please Hitler. When he visited him, he always wrote to my mother that “I was placed to the right side of Hitler at the dinner”. While, at home in Krakow, the most horrendous crimes were committed on the same day. For me, his famous sentence was – Hilde, my nanny, told it to me when I interviewed her – he told to his deputy, Josef Bühler, on the phone at a new year’s eve party: “Please wait with the executions till I am back home to Krakow!”

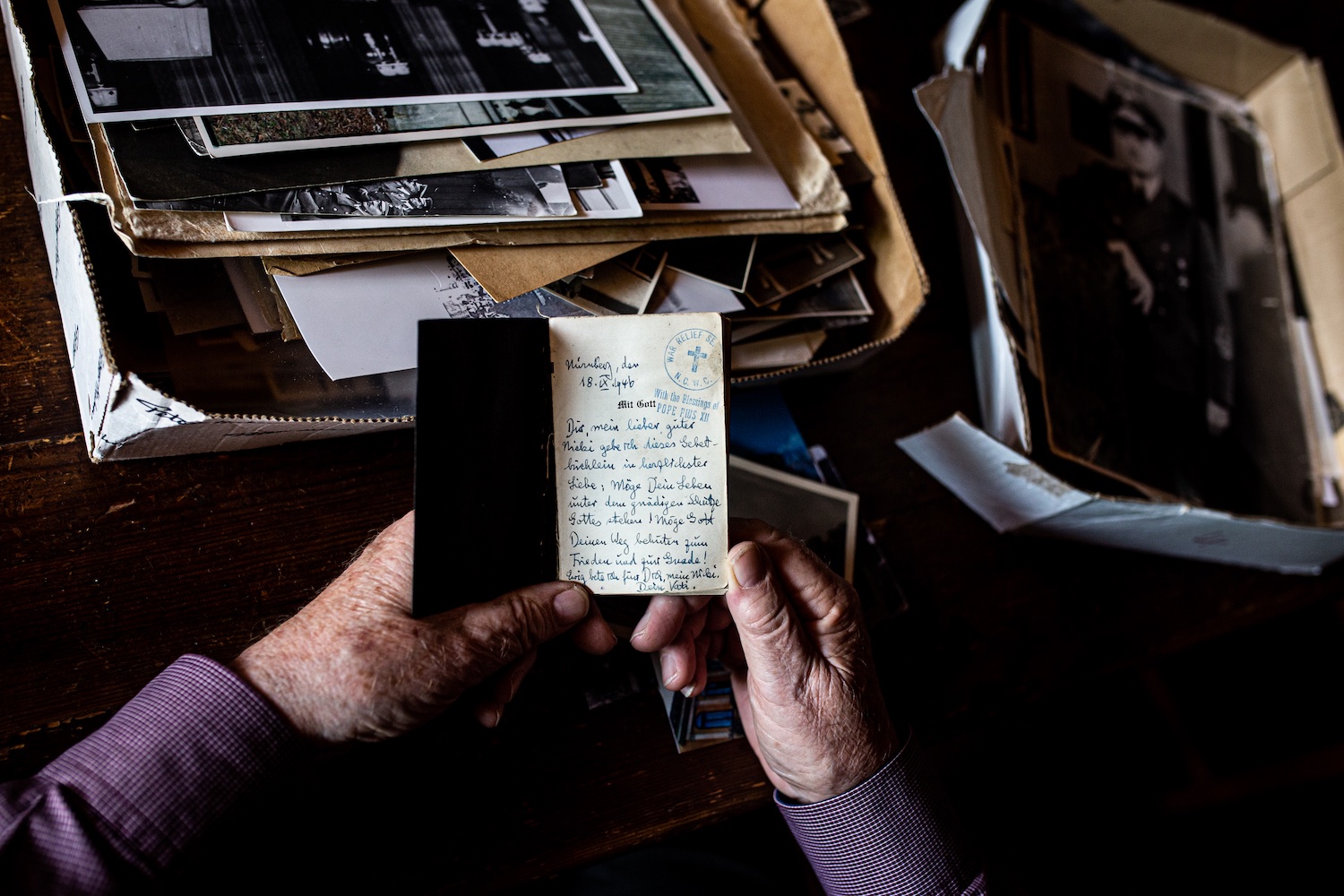

– You have often recalled your last meeting with your father in the Nuremberg prison in 1946 when he promised to celebrate Christmas together, just days before he was hanged. You also said you knew it was a lie but you have few pre-1945 memories. Did you became that conscious in just one year?

– Every German family was hit by the war – fathers, sons, uncles did not come back. I had a father who was arrested and even a kid knows that detainees might have done something wrong. I also saw my mom being upset about the imprisonment, the newspapers showing my father sitting in the first row of the Nuremberg trials and I heard his lawyer, Mr. Seidl, in the summer of 1946 explaining to my mother that: “Mrs. Frank there will be no chance, your husband will get a death penalty because the proofs are so strong against him.” All 5 children knew it and having this in mind, although I was only 7, I knew I was having my last encounter with my father. Then he started to lie. It was really hurting for a child.

– Was there a moment when could realized his verdict was rightful?

– It started before it was handed out. In autumn 1945, German newspapers published pictures with corpses with the subtitle: “Polen” (Poland). This was shocking for me and for my brother, Norman, who said to my mother that if those pictures had been authentic, our father would have no chance to survive.

– Why have you decided to follow your father’s footsteps? It must have taken decades of research from your life.

– Let me start from the beginning. The best thing that happened to me and which made me different from my four siblings was that my father, in the first years, did not acknowledge me as his son but as the son of his best friend: the Galician governor, Karl Lasch. My mother was an experienced lover, her other parallel secret relationship was with Carl Schmitt, the lawyer. When I was running around the table the Warsaw’s Belvedere Palace – where I have interviewed president Lech Wałęsa almost 50 years later –, my father always mocked me: “What do you want little stranger? You don’t belong to our family.” I wept. If you are being refused by one of your parents, you have only two choices: you can either become a ruined character – running from one psychiatrist to another or committing suicide – or you build up your subconscious. The latter happened to me.

The only positive scene between me and my father was once at the Wawel when he put his shaving foam on my nose. Growing up, I said to myself that I wouldn’t let my life to be ruined by my father – which he did not.

When I met my wife at the age of 22 at the university in Munich, I told her that once upon a time I would write about my father. And even though I met the relatives of my parents, it was never the topic of my life – the topic was to become a famous film director which never happened so I became a movie writer then a journalist. I really started to research after the age of 40 after I was hired by Stern magazine in Hamburg: whenever I was on duty in Germany, I always met with the former friend of my father – but only after I interviewed some famous German poet.

– What was your wife’s reaction when you told her who you were?

– She just loved me. I never understood why.

– When did you return to Poland?

– It was only in the early 1980s. As a reporter, I have visited Krakow and Warsaw. It was very moving as it was first time I saw again the Wawel and our weekend castle in Kressendorf (now Krzeszowice). It was moving but it also grew the rage against my father because of the crimes I became aware of in the meantime.

To the right: Mrs. Frank, accompanied by her son Niklas and her daughter Brigitte, arrives to say farewell to his husband

– Why do you feel obliged to still speak about them?

– Speaking about the truth is the best thing I can do. I have never urged anybody to invite or interview me but when I have the occasion, I would never lie.

– Haven’t you suffered enough from your father’s memory?

– I have suffered only because of the innocent people we have killed. That makes me angry because there is no day when you don’t find something in the newspapers which is not related to the Nazi times. The anger always comes up then.

My wife is coping with cancer – we have never given even this chance of survival to those innocent people.

– As a man in his 40s, what would be your father today?

– He was a very educated person who told his psychologist in Nuremberg that he always had two personalities: the one that wanted to become a politician and the other wanted to become a law professor. If he had survived the war as an ordinary citizen, probably he could have become a successful lawyer. Living in Munich, he would be voter of CSU.

– In Nuremberg he famously said that “a 1000 years will pass and still this guilt of Germany will not have been erased”. Was it an honest statement?

– For me it was a trick to impress the judges. He said it when he was asked whether he was personally involved in the operation of extermination camps, and this is how he distributed responsibility onto the shoulders of 80 million Germans, minimizing his personal guilt. I don’t believe him, even if he became religious in Nuremberg and was re-baptized by the Catholic church. His priest, Father Sixtus O’Connor, told me when I later interviewed him that he suggested to his Protestant colleague that “I am not sure whether Hans Frank is really so religious as he acts”.

– Are you Christian?

– I was brought up Catholic but quit the church at the age of 27. For me they are ridiculous.

– So you are not obliged to believe in forgiveness…

– … it is something else. It happens between human beings. But I can’t forgive my father…

– … and you are not obliged to fulfill the commandment of respecting your father either.

– Even the biggest atheist has the Ten Commandments in his brain and heart. Respecting your father means not to excuse him. I respect my father through his misbehavior and by putting him in front of my tribunal. This is my respect.

Photos by Szabolcs Vörös