“It’s worth appreciating because it works” – Distinguished Dutch journalist and author on the parallels between the EU and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

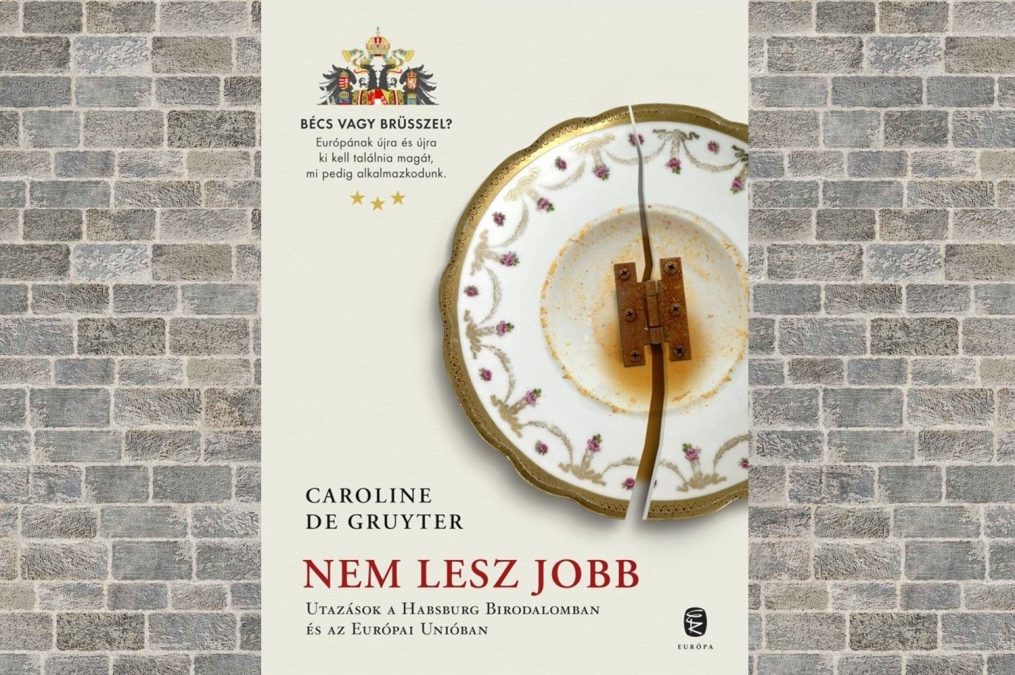

“The rebellious Hungarians were constantly fighting against ‘Viennese rule’ but had no intention of breaking away from the empire; it was worth staying in. It says a lot about them that they are now doing the same”, writes Dutch journalist Caroline de Gruyter in her recently published book ‘It will not be better: Travels in the Habsburg Empire and the European Union’, published by Európa Könyvkiadó in Hungarian. The book, which has been a great success across Europe, is not just a frothy Habsburg nostalgia: it is an investigation into the parallels between the long-gone dualist state and the EU, the virtues and drawbacks of benevolent empires, their architecture, gastronomy and literature. Caroline de Gruyter was first interviewed in the Hungarian press by Válasz Online about her adventures in Central Europe.

Az interjú eredetileg magyar nyelven jelent meg

-The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was a state with a unified army and civil service, headed by an Emperor-King who ruled by the grace of God. What does it have to do with the European Union, a voluntary association of nation states?

–There are indeed important differences, but there are also remarkable similarities. In the EU, very different nations live together in a geographically delimited space and are always at loggerheads, especially in times of crisis. Their leaders are therefore constantly forced to compromise. This is exactly how the Habsburg Empire worked. Count Eduard Taaffe, Prime Minister of the Austrian half of the Monarchy from 1879 to 1893, was once asked what the essence of his job was. He replied: ‘fortwursteln’ – i.e. pottering around without a clear purpose or plan. Jean-Claude Juncker, former President of the European Commission could also have said these very words. The leaders of empires with many conflicting national, regional, economic and ethnic interests spend a great deal of their time making compromises. They work to ensure that everyone remains on board with the project.

– Another difference: in the EU, it is ultimately the heads of state and the governments of member states who decide, while in the Monarchy it was the Emperor.

– But he too had to take into account different interests. When the Hungarians thought they were spending too much on the common army and supplying too many soldiers, even Franz Joseph could not just ignore their grievances. And although the dualist system was much criticised by contemporaries, subsequent analyses are much more understanding. I have read extensively about the Ottoman, Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian empires of the time. The latter was not a coloniser, it did not conquer foreign territories except for its occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. It was, as they say, a ‘benevolent empire’. I think this description fits perfectly well for the European Union, which is often accused of being incapable of exerting force. Unlike other global or regional powers, it does not wage wars. The Habsburgs managed quite well with this strategy, and although they generally lost their wars, they somehow kept the empire together. Despite all the agitation, the nations that made up its constituent parts had a stake in its survival. Just like today: look at the policies of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. He is sharply critical of the Commission, the European Parliament and his partners, whilst 90% of the time he votes through everything, even the sanctions against Russia. True, he refrains from telling his voters this.

– “The rebellious Hungarians were constantly fighting against ‘Viennese rule’ but had no intention of breaking away from the empire; it was worth staying in. It says a lot about them that they are now doing the same” you say in your book. Is saber-rattling not a legitimate strategy for defending your interests? Cyprus, for example, vetoed sanctions against Belarus in 2020 because they had a problem with the Turks, yet no one called them traitors to the EU.

– Yes, this tactic is used by others, but that’s not the problem. Hungary has now isolated itself because it repeatedly vetoes common foreign policy decisions. Furthermore, the Hungarian government has no allies. The war in Ukraine has changed everything. In ‘peacetime’ we fought one another, but now it is time for unity – and the Hungarian prime minister’s maverick policy no longer fits. European values, the rule of law and democracy have become much more important now that a power that denies them has started a war in Ukraine. The Hungarian government’s situation is perfectly summed up by the footage of the Hungarian prime minister standing alone at the last European Council. Orbán is also using his conflicts in Brussels to strengthen his domestic political position. No doubt, this tactic is used by others, but none as aggressively as the Hungarian prime minister. Of course, this approach has always been part of the populist toolkit. It must also be said, however, that in the past the EU was too concerned with technical issues, such as fishing quotas and chemical directives. So maybe it’s not a bad thing that there is more emphasis on important issues and values, even if these subjects are often voiced by populist politicians.

– What did your research lead you to: will the EU end up like the Austro-Hungarian Empire?

– To be honest, I don’t know. I wrote the book before the war in Ukraine but the conflict that started in 2014 was already casting a shadow. By the end of my research, I came to the conclusion that it was war and not ethnic nationalisms that ended the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Various irredentist movements existed, of course, but they were too weak to dismantle the empire. Without denying the strength of nationalist demands, I would nevertheless place greater emphasis on the suffering of the war. By the end of the First World War, people were starving all over the Monarchy and law and order had broken down. Most people felt that this state could no longer take care of its citizens and that it had to be got rid of. This is a danger today as well: the European Union would be less stable if people believed that they could expect nothing from it.

– Paradoxically, is it not precisely in times of crisis that the EU is at its strongest? For example, during the coronavirus epidemic, the common purchase of vaccines enabled them to get them at lower prices benefitting smaller states as well. For another, to restart the economy even the Germans accepted the need for previously unthinkable joint borrowing..

-I agree, but let us ask why this happened. Despite all rumours to the contrary, the EU is run by the nation states. In more peaceful times, governments do not want to hear of such moves, because they are seen as compromising their sovereignty. But on the edge of the abyss, they always realise that they can do more together than apart. Crises are loved by the press, especially in the US and the UK, with headlines that predict the ‘end of the EU’. During the euro crisis, for example, member states voted through everything from strict controls of banks to constraints on national budgets. Previously they had refused to do so. Why is that? Because they wanted to avoid the collapse of their common project. The constant negotiations, the many half-solutions and last-minute compromises are exhausting, but that’s how the EU works. And that’s how the Habsburg Empire worked. Franz Joseph, for example, agreed The Compromise with the Hungarians in 1867 after a series of military defeats and domestic political failures had left no other viable solution.

| Caroline de Gruyter is a Brussels correspondent for the NRC, one of the most reputable Dutch newspapers, and her analyses regularly appear in EuObserver, Foreign Policy and other publications. She has lived and worked in Gaza, Jerusalem, Geneva, Vienna and Oslo. He has received several awards for her journalism and is a member of the European Council on Foreign Relations. |

– In your book, you write that one of the sources of misunderstanding in the EU is that Western Europeans talk about the future, while Central Europeans talk about the past. If we look at the wars raging on Europe’s immediate borders, Ukraine, Nagorno-Karabakh, Israel, we see the return of history…

– You are right. We didn’t pay enough attention after the 2008 war in Georgia or the 2015 annexation of Crimea. The French continued to sell arms to Russia and the Germans built Nord Stream 2. The current war in Ukraine proved that the nations of Central Europe were right to warn of the Russian threat – I find it remarkable that it was the two former members of the Monarchy, Austria and Hungary, that were far more lenient with Moscow. However, Hungarians have experienced disdain by the West.

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas says that even 20 years after joining the EU, Central Europeans are still ‘new member states’. It never occurred to anyone to call Sweden a new member state two decades after they joined the EU.

History has indeed returned, and this paradoxically strengthens the unity of the EU. Something similar happened in 1914 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Not only in Vienna and Budapest, but also in Prague, Zagreb and Ljubljana, people queued up in front of the conscription offices. They felt they had to defend their common homeland after the assassination of the Crown Prince in Sarajevo.

– As an outsider, you were amazed at the legacy of the Monarchy, and in your book you say that it is still living on. Why?

– When I moved to Vienna, it was impossible to escape the legacy of the Monarchy. Theatre performances in Vienna, for example, still end at ten o’clock, because Franz Joseph liked to go to bed early. Almost everyone has Czech, Polish, Hungarian or Slovak ancestors in their family, and the architecture of the city is also reminiscent of the period. The past lives on in people’s minds. I recall the story of an interview with Charles IV’s widow, Zita, shortly before her death in 1989. The true socialist and republican Austrian journalist referred to her interlocutor as ‘Her Imperial and Royal Highness’ like it was most natural thing to do. I was also struck by how differently the European Union and our common European history are viewed in different countries, and how much this depends on the past of the country in question. In the Netherlands, we hardly learn anything about Central Europe, about the Austro-Hungarian Empire – we only know about Sisi. On the other hand, we know everything about the Atlantic world, the British, and our attention has always been turned in that direction. In comparison, in Vienna or Budapest, you have a completely different approach, and this also influences the way in which, for example, states conduct politics in the European Union.

– Did you feel the same in Hungary as in Vienna?

– I was in Budapest two weeks ago for the book festival and the legacy of the empire was immediately apparent, as it was in other former cities of the Monarchy. But while in Prague and Krakow, for example, progress is visible, Budapest is in bad shape. The main railway junctions of all the major Central European cities are in much better condition than Budapest’s Eastern Railway Station, and its houses are in a state of neglect that is no longer visible in Krakow, Warsaw and Prague. However the gastronomy is still very monarchical, and here just as much as in Vienna you can hear piano playing through open windows.

– You have an amusing story that in the early 2000s you saw then Commission President Romano Prodi in IKEA in Brussels and nobody recognised him. A portrait of Franz Joseph once hung in every post office and railway station; isn’t one of the EU’s problems that there is no one to identify with and therefore nothing to love?

– I think you would recognise Ursula von der Leyen among the kitchen furniture and double beds today. The constant crises and threats have increased the EU’s visibility and recognition. For a long time, the slogan was to depoliticise the European Union, but we have realised that things don’t work like that. In an uncertain and dangerous world, political decisions and value choices cannot be avoided. Look at President Zelensky’s determination to bring his country into the European Union. If others find our model so attractive, we in the EU should sometimes stop whining. People are beginning to understand that the peace and prosperity that the EU provides is not a given. Twenty years ago, about 50 per cent of EU citizens were happy to see their country in the EU, with the rest being generally indifferent. Today, around 70 per cent are satisfied – they may not like the way the EU works, but they feel much better off as members.

– You refer to the pan-European thinkers between the two wars, many of whom grew up in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and their influence on the statesmen who laid the foundations of the EU after the Second World War. Otto Habsburg also believed that there was continuity between the two ’empires’. Would the EU be heir to the Monarchy?

– With a certain irony, I would say that ‘fortwursteln’, or pottering, certainly links the two worlds. We understand that we are too diverse on the continent. We need a European framework to keep us safe. Great writers such as Joseph Roth, Stefan Zweig, Robert Musil were incisively critical of the Habsburg world. Their texts seem modern and familiar, because they could have been writing about the EU. But after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they felt remorse for their harshness. Suddenly the benevolent empire seemed not so bad after all. The European Union was conceived to avert a war that is now knocking on our door. The Middle East is also burning; I lived there for five years, so I can assure you we cannot escape the consequences of what is happening in Israel and Gaza. These constant compromises in the EU are not ideal; utopians are always dreaming of something grand, of a perfect system, and cynics are quick to mock the EU. But it is worth appreciating because it works.

Translated by Gergely Papp

Title photo: Caroline de Gruyter in a café in Vienna